The Refugee Hotel is at times an emotionally charged history lesson.

The Refugee Hotel is a fictionalized story based on playwright Carmen Aguirre’s experiences arriving in Canada with her family during the brutal military coup in Chile. As Aguirre said in her recent interview, it also draws from the experience of others and what she called “the mythology surrounding Chilean refugees”.

Its central story focuses on a family of Chilean dissidents who escape their home country to Vancouver. The mother has been secretly active in the resistance to Augusto Pinochet’s regime, the father a believer in more peaceful resistance. Reunited with their two children in Vancouver, the couple look to rebuild their lives while justifying their individual responses to the crisis in Chile.

Finding themselves temporarily housed in a hotel for refugees, the family is soon joined by an assortment of other men and women fleeing Chile. They are helped by a well-meaning social worker, a Canadian sympathizer, and an irascible front desk manager who, not surprisingly, grows to love the Chileans placed in his care.

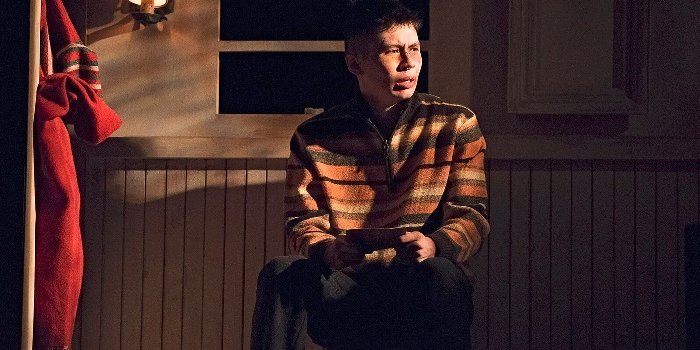

As the family and other exiled residents adapt to their new life in Canada, the horrors they endured during the coup are revealed. These scenes are intensely realized. As Manuel, Mason Temple gives one of the best performances of the night in a particularly moving, dark and vivid recounting of his prison torture.

While each professes a loyalty to their homeland, a belief in the cause, and a desire to help those still remaining, Aguirre quickly abandons these political and social ideals with the realities of adapting to a new country. This discarded theme is as stark as the just-as-brief condemnation of the idiosyncrasies of capitalistic life.

Oddly, it is the children who the playwright places in the position of providing a contrary voice. While the other characters recount the horrors of their torture, it is up to the young son to question whether what each has done, including his parents, was right. At one point calling them criminal for having joined the resistance, it rings a little hollow. The effect diminishes any opposing view and does little to reinforce Aguirre’s condemnation of what took place.

No doubt some audience members will question the Chilean characters played by non-Latinx actors, justified in this production as a learning experience for these Studio 58 students. While there is little doubt a Chilean actor would bring authenticity to the roles, for the most part this is a non-issue. There is however, some confusion around the age-appropriateness of some of the roles, justified in the same vein due to the show’s predetermined cast drawn from available students.

Particularly compelling are the very watchable Logan Fenske and Elizabeth Barrett as husband and wife. Their scenes together are some of the most fully realized and their fear separately and apart was sometimes breathtaking. It is perhaps not so surprising though given how little time is spent in learning more about the others who end up at the hotel.

Billed as a dark comedy, ironically much of the comedy is at the expense of Aguirre’s white characters: the do-good social worker with her mix of English, French and Spanish; the effeminate gay front desk manager; and the earnest young sympathizer who never gets his pronouns correct. While none are mean-spirited, they remain stereotypes.

Some of the action is punctuated by cueca dancing performed in traditional dress by Matthias Falvai. Perhaps it is meant as a nod to Chile’s roots, or a somewhat esoteric acknowledgement of its courting ritual? Aguirre never explains his presence, or why her characters acknowledge the dancer’s existence.

Yvan Morissette provides a multi-layer set allowing Aguirre, who also directs, a number of levels on which her actors to play. While it felt crowded at times, painted in a monotone cream is does give the effect of a hazy memory. Costume designer Elizabeth Wellwood gives us 1970s appropriate costumes with a mix of representative Chilean dress.

There is some great information in the play’s program that is required reading. I highly recommend you take the time to read it before the lights go down. Better yet, you can read the show’s study guide online before you go.

The Refugee Hotel written and directed by Carmen Aguirre. A Studio 58 Langara College production. On stage at Studio 58 (100 West 49th Ave, Vancouver) until April 9. Visit https://studio58.ca for tickets and information.